A visit to the Watts Museum and Gallery

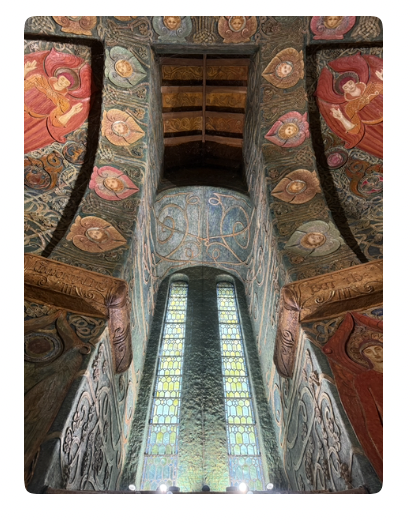

Just after Christmas I drove from Oxford to Compton, Surrey to take in the art of G.F. Watts at the dedicated Watts Gallery. It’s well worth a visit with plenty to do and see, especially to take in the remarkable chapel which reminds me of mid-German churches and also the peculiar yet beguiling tone of Rudolf Steiner.

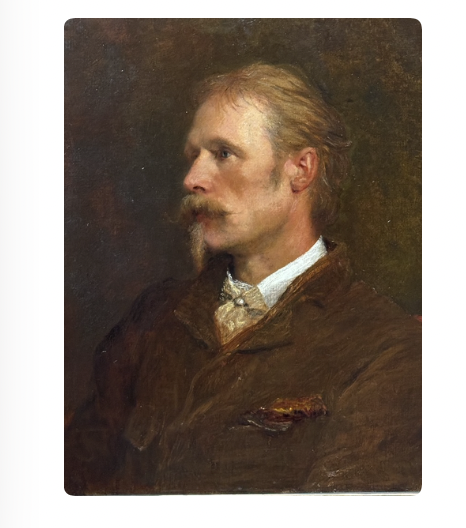

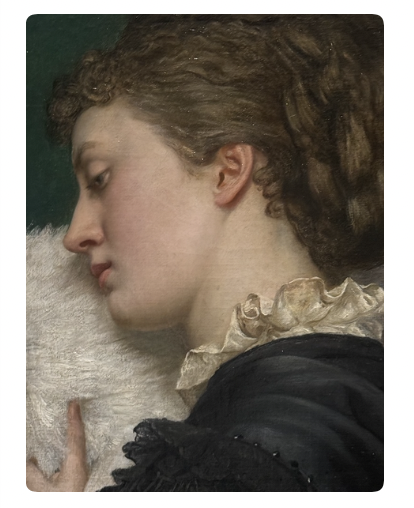

I found Watts’ work to be somehow patchy - in some areas, exquisite yet in the same room and even in the same painting, a moment of ‘fudging’, or misreading. His works can go from exquisite and masterly to oddly lacklustre and almost amateurish within the space of a canvas: the first painting here is very beautiful despite it being a simply portrait.. and yet I’m drawn to some sense of disappointment when my eye is drawn to an oddly proportioned ear. The same goes for many of his works.

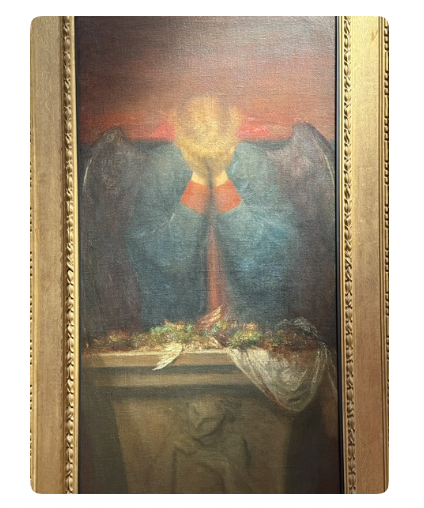

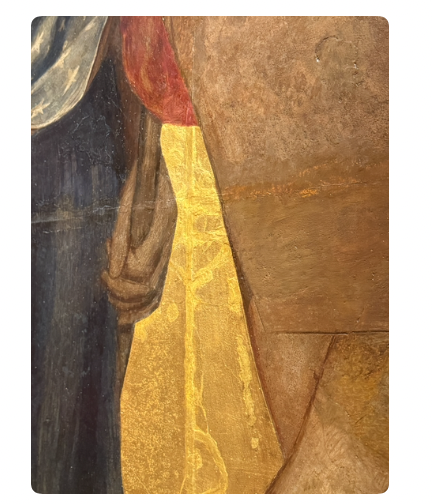

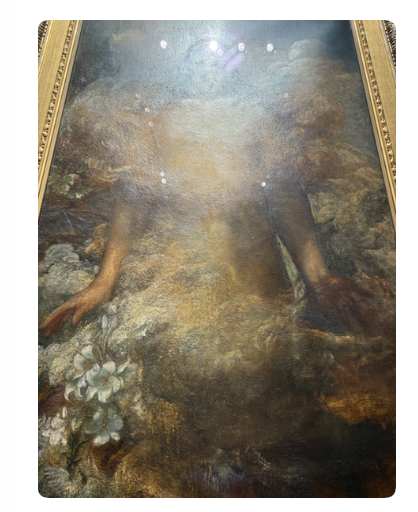

Yet at some point it’s almost as though his subconscious accepts the element of imperfectionism and he embraces this particular defect by either ignoring it or even removing it and replacing it with something deliberately undefined. Walking into the room with the three paintings as a triptych is an example of this. The brushstrokes are rough, the detail of other works lost in a peculiarly earthy and uncultivated working of the paint.

Faces are hidden as if almost wiped clean off the canvas. Hands are bold, out of proportion, ugly and yet brazen and such unarticulated parts become a more coherent and positive overall part of the expressive nature of the works as a whole. I sense that a lot of his works move towards symbolism; there’s a real sense of realism turned more mystical.

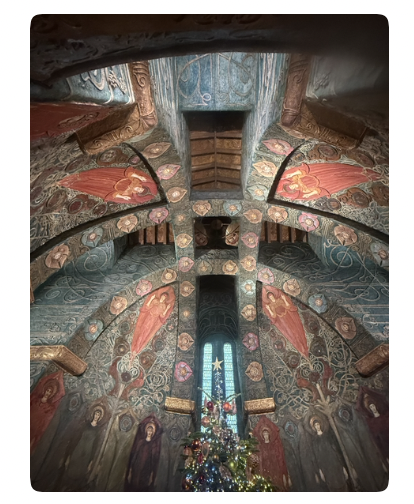

Meanwhile in the chapel Mary Watts, his wife just goes for it: a woman who reminds me somewhat of my own.. socially and politically determined, driven and yet also capable of creating and applying herself to the art form in a way that is less self-searching than her partner and more determined to create something that has to be borne from her very drive for creating change. It’s an out of the box, get up and do it kind of visionary creativity, like a highly sharpened blade of a sword cutting through all expectations through her own experience and applying the skills hewn from the way she sees things to create something of immense power. It’s not perfection; it’s a singular vision which is performative and taken to completion. It stands alone.

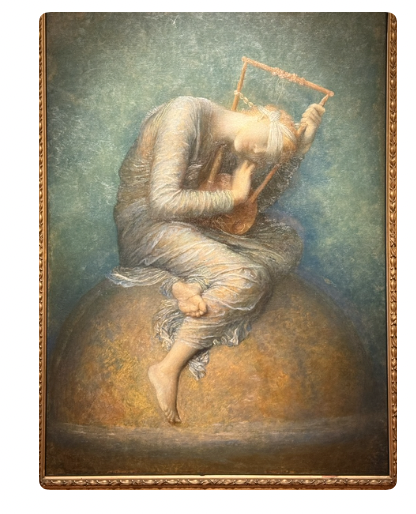

G.F. Watts, in comparison, seems to have been driven from early on by expectation and a slightly muddled sense of what must be created in order to get ‘it’ right; a feeling that his skills must be shaped and perfected by a myriad of unformulated rules and practices akin to those artists around and before him. I sense that as he progresses his work becomes more unruly and un-ruled, freeing himself from a style that seems mostly formed of a somewhat kaleidoscopic and perhaps fear-tinged vision of what he should be doing.

By a peculiar twist of freeing himself from his rigorous attempt to get things ‘right’, his works loosen, become unapologetic and begin to embrace imagination and imperfection. By a twist of his thinking, which I wonder was a subconscious realisation that Mary held the true key to understanding her primordial creativity, focusing on her working with others, G.F.’s approach to how he creates becomes less constrained, more dreamlike.

It’s as though his female companion, with her womanly determination to nurture, create and forge despite the still-existing social barriers and obstacles, allowed him to realise that his work, though technically beautiful in many ways, wasn’t working and wasn’t quite working. Perhaps this is simply because his vision was bound by what he felt bound to do.

In contrast, Mary could have been bound by the constraints of societal or artistic expectations but realised her own vision much more powerfully and much more quickly than he did and, in a delightful paradox, it’s her work which shines much more brightly than his and she who unlocks the secret to articulating the essence of genuine artistry. His work, by comparison, with all the societal benefits of his position as a male artist, seems to fumble, twist, turn, and never quite makes it to a realised example of his true inner vision.